Rebecca Saive from Germany finds it annoying when Dutch colleagues ask her whether she is an academics or an entrepreneur. Why should you have to choose either one or the other? At the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), where she worked for four years, scientists who establish startups are often held in higher regard. We must get rid of that compartmentalised thinking, says Saive.

At the age of three, Saive already knew that she wanted to be a professor. Her parents were chemists and because they could not always find a babysitter, they sometimes had to take young Rebecca along to the laboratory at the University of Heidelberg and to appointments with “The Professor”. ‘My parents always spoke about him with considerable respect and they called him “the man who knows everything”. Besides that, he was also incredibly kind.’ Although later, she also thought about being a teacher, vet or professional dancer, her dream of becoming a professor remained. Now she has a tenure track appointment and so, if all goes to plan, she will soon be able to call herself a full professor. That took a bit of time. Assistant professors in other countries can simply call themselves a professor, but that’s not the case in the Netherlands. This is just one of the many cultural differences that surprised her as a foreigner, but she will tell us more about that below.

Rebecca Saive is professor in Applied Physics in the Inorganic Materials Science group at the University of Twente, where she has her own research group. She was the founder and CTO of ETC Solar, but she recently left the company. Saive is now working on new solar energy ideas for which she also seeks commercial applications.

''Many Dutch academics still think too much from the perspective of traditional disciplines: physics, mathematics, chemistry or mechanical engineering.''

From an early age, Saive was determined to make solar panels better. She gained her doctorate from the University of Heidelberg for her research into charge transport in solar cells and subsequently worked at Caltech on light-matter interaction. She stayed there for four years. A brief search brought her to the University of Twente, in part because she was so impressed by the MESA+ NanoLab. ‘I discovered that it had one of the best university clean rooms I’d ever seen. The clean room has a lot of different types of specialised equipment, which is well maintained and gives very high-quality results.’

Genuine improvements

Saive never imagined that she would be the co-founder and CTO of a startup; that simply was not on her bucket list. She has, nevertheless, always taken the collaboration between companies and universities for granted. At the laboratory in Heidelberg, various universities and companies worked together and she did an internship at the chemical company BASF. ‘Many of my regular colleagues came from industry but they were never interested in why something worked. I, on the other hand, wanted to first of all truly come to grips with why and how something worked and then use that knowledge to discover something that was genuinely better and not just an incremental improvement.’ At Caltech, the interwovenness between the university and the private sector was even more self-evident. ‘There, fundamental researchers are often also entrepreneurs. Even more so, you enjoy a better reputation as a researcher if you also initiate startups.’ However, that does not mean that there are never any discussions about conflicts of interest at Caltech. For example, in principle, you are not allowed to invest research money in startup activities, but startups can make use of university lab facilities. However, then the question is for how long; at what point is a startup considered mature enough to leave the university fold and fund its own research? That subject regularly comes up in negotiations. And things are no different at the University of Twente. Saive would like to make more use of the MESA+ NanoLab than she is able to at present. However, due to stringent rules limiting use, many experimental (student) projects are not allowed.

Arduous negotiations

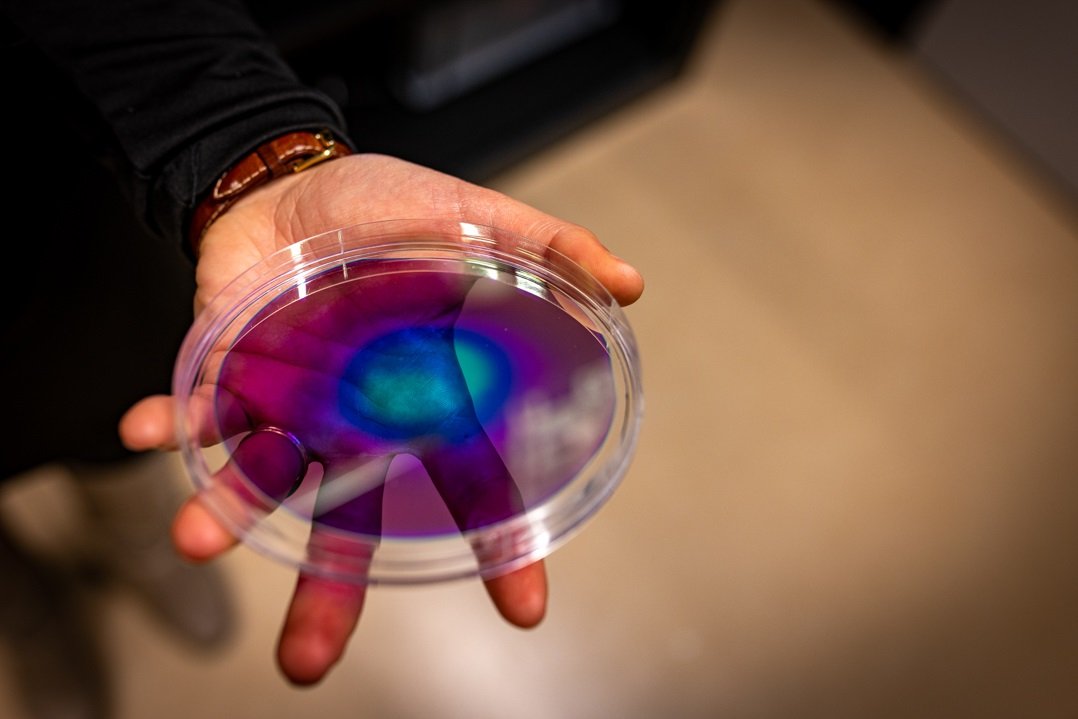

During her stay in California, Saive invented a method to make the silver gridlines on solar panels thinner and triangular in shape. Silver reflects light, whereas you want a solar panel to absorb as much light as possible. Changing the size and shape of the silver grids can increase the efficiency of solar panels. Together with her supervisor Harry Atwater and Dutch former Masters student Thomas Russel, she co-founded a start-up on the idea. They developed the technology further and wanted to also establish an official startup at the University of Twente. However, that plan initially had a bumpy ride. Saive contacted Novel-T, the technology transfer office of the University of Twente, Saxion University of Applied Sciences, the Province of Overijssel and the municipalities in the Twente region but the initial negotiations did not proceed smoothly. ‘I did not know the system yet, nor the people that are part of it. During the first meeting, they said that they wanted sixty percent of the shares in the startup. I was really taken aback by that and found the idea ridiculous. Only later did I understand that what people say in a meeting is not already set in stone. And that is also something I notice in conversations with other Dutch people. What often seems to be a hard demand at first, often proves to be open to discussion at a later stage. But on the other hand, I’ve also noticed that people do not always keep their promises.’ Saive failed to reach an agreement with Novel-T, and because Caltech owns the intellectual property and not the University of Twente, she was free to seek funding elsewhere. ‘Only later did I understand that the percentage of shares depends on the amount of support you receive, to what extent the university owns the intellectual property and that, for example, the percentage can quickly be brought down as the company grows.’

Meanwhile, Saive has left the company because it has matured into the manufacturing stage, which is not as interesting for a physicist as the initial stages where hardcore physics and technological creativity are paramount for advancing. Now, she is working on two new ideas for which she also sees commercial potential. One is a different method for producing triangular gridlines in solar panels and another is a completely new idea, namely a sort of reflecting screen that focuses solar rays and transmits these to a solar panel. For these ideas, she will once again approach Novel-T. ‘I now enjoy a good relationship with them, and that has also helped me a lot in applying for patents. Novel-T has an outstanding track record, genuinely wants to be one of the best TTOs in Europe and tries to be as supportive as possible.’

Besides these applied projects, she has also received a Vidi grant from NWO for research into combining solar energy with piezoelectric materials so that solar energy can be used for applications that involve movement. Before her appointment at the University of Twente, she worked as a postdoc and senior researcher at the California Institute of Technology.

She was a finalist for the EU Prize for Women Innovators in 2020, received a European “Innovators Under 35” award from the MIT Technology Review in 2019 and was also selected for the MIT global “Innovators Under 35” in 2020.

''I discovered that the MESA+ NanoLab had one of the best university clean rooms I’d ever seen."

Gain in-depth knowledge first

Although the University of Twente is a trailblazer in encouraging entrepreneurship, Saive still thinks there’s plenty of room for improvement in the Dutch attitude. For instance, people still regularly ask her whether she is an engineer or a physicist? Even though the distinction is less important for her. ‘Many Dutch academics still think too much from the perspective of traditional disciplines: physics, mathematics, chemistry or mechanical engineering. That’s absolutely fine when it comes to teaching; I’m all for gaining in-depth knowledge and making sure you first of all really get to grips with your own discipline. That’s why I’m less keen on modern hybrid studies that combine several disciplines. Of course, there are some exceptions to this but, in general, these students lack the skills and fundamental knowledge needed to come up with genuinely groundbreaking innovations.’ In Saive’s view, you should first study a discipline in depth, and then you must be brought back to the surface, so to speak, so you can focus on using that knowledge to make a contribution to society. ‘That transition will take place automatically when you study modern subjects. However, most physicists are mainly curiosity-driven. Thanks to the culture in the United States, you’re automatically drawn out of your bubble. For example, you soon need to answer certain questions during presentations: Have you done a feasibility analysis? Are the materials you’re working on truly affordable and available? Is it possible indeed to scale this up to mass production?’

Saive has also devised an idea for drawing fundamentally oriented students and PhDs out of their cocoon: a pitch competition. So don’t begin by getting them to think about a startup because then you’ll scare most of them off. Instead, get them thinking about how they could contribute to the major societal challenges. For example, if you were to offer a visit to a foreign congress as a prize, there’s a high chance you’d persuade most of them to take part.’ According to Saive, this approach would allow even the most fundamental academics to make an impact with their research.

Three points for further reflection and discussion:

- Shouldn’t we do more to embrace and reward scientists who are also entrepreneurs?

- Why do we ask scientists to choose between their business or the university?

- How can we get curiosity-driven scientists to think about impact at an early stage of their research?