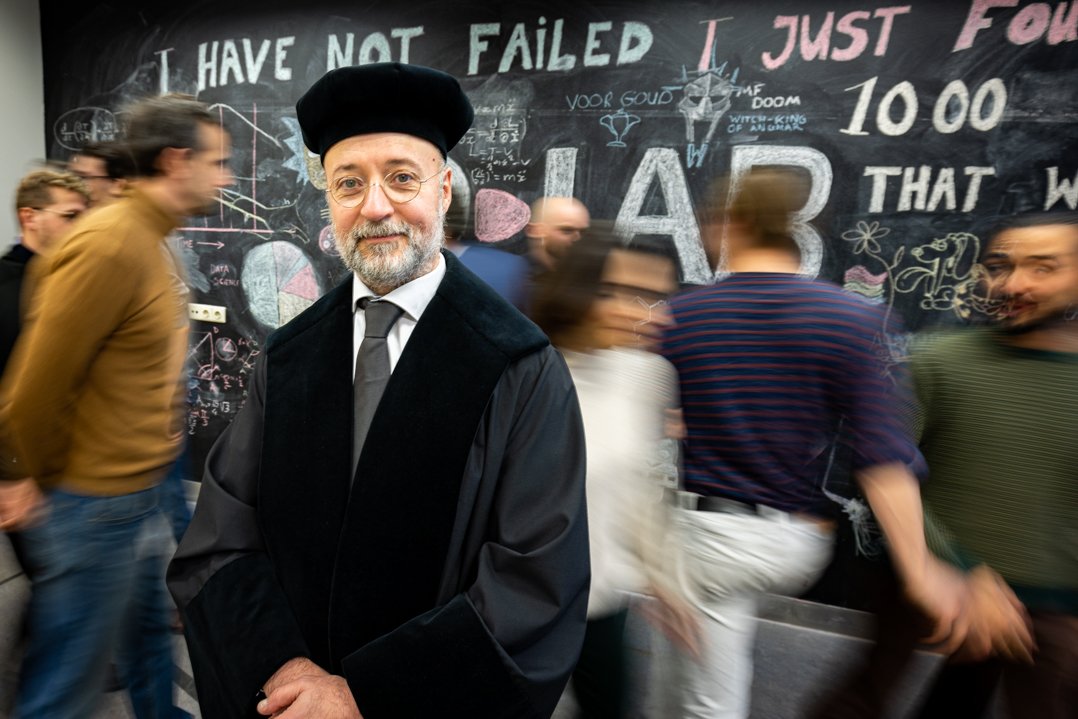

Davide Iannuzzi does not consider himself an active scientist anymore. Nor does he think he was ever an entrepreneur. And yet, he has set up a successful company, launched and run the Demonstrator Lab at VU Amsterdam, served as Director of Valorization for its Faculty of Science and in January 2022 was appointed his university’s first Chief Impact Officer. He is undeniably an entrepreneurial spirit, even if he has taken on more of a managerial and mentoring role.

Technology looking for a market

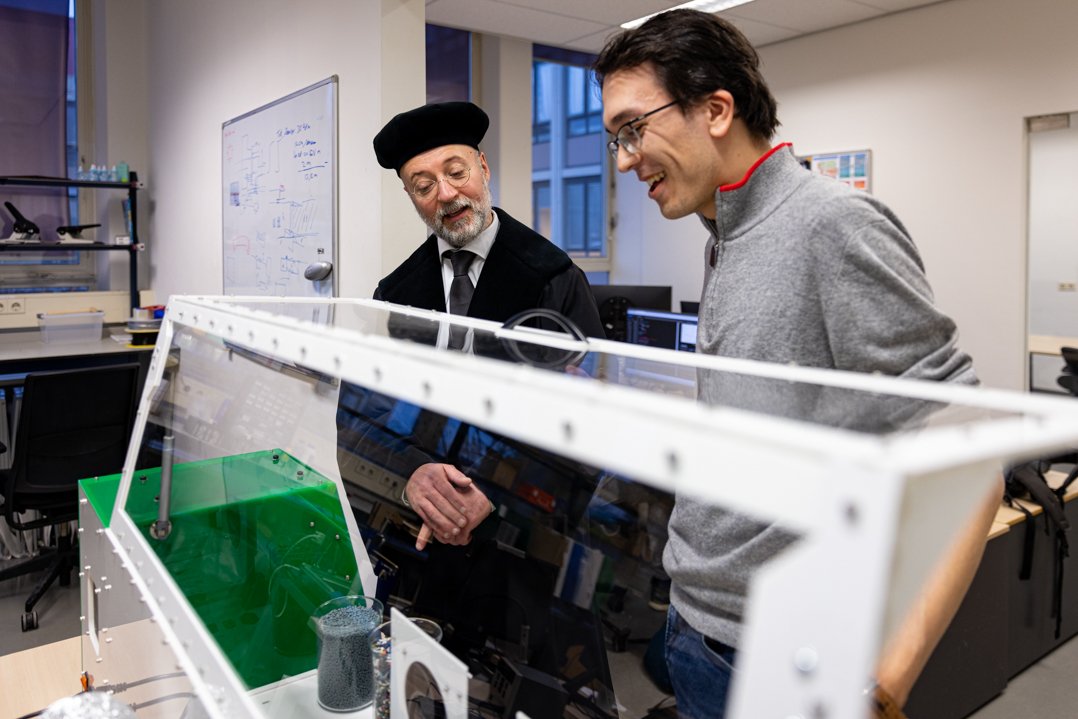

In 2005, fresh from post-doctoral work at Harvard, Davide Iannuzzi came to Amsterdam with a Vidi grant from Dutch Research Council NWO to do experiments in quantum electrodynamics. Because the set-up he had for the measurements involved didn’t do what he wanted, Iannuzzi developed a new sensor based on microtechnology and optical fibres – and found he could now measure “pretty much anything”: vibrations, accelerations, temperature. He decided to patent the technology and make it available to others outside his lab. Rather naively, as he looks at it in hindsight, he thought he could just get the patent and sell it to a company to bring it to market. “That never works”, he says today. Instead, he was able to secure a couple of grants to improve the device from a technology point of view.

The turning point came in 2011, when he met entrepreneur Hans Brouwer and together they founded Optics11. “It was technology looking for a market”, Iannuzzi says. So they built a very basic first unit to demonstrate the technology in different markets. As it turned out their sensor was especially good at measuring the mechanical properties of biological tissues and cells. It was simple, easy to use and compatible with the natural (moist) environment. They hired a CEO and grew the company to almost 15 people before attracting their first outside investment in 2016. In September 2022, Optics11 raised another EUR 10 million to scale the company.

Davide Iannuzzi is Chief Impact Officer and Professor in Experimental Physics at VU Amsterdam. He got his physics degree from the University of Padova in 1995 and his PhD from the University of Pavia in 2001. He was a postdoctoral research fellow at Lucent Technologies Bell Labs and Harvard University in the US, before joining VU Amsterdam as an associate professor in 2005 and becoming a full professor in 2013. Iannuzzi also holds an MBA from TIAS School for Business and Society in Tilburg.

Iannuzzi co-founded Optics11, a company that markets powerful table-top nanoindentation instruments to measure complex biomaterials, in (surprise) 2011. Five years later he launched the academic pre-incubator Demonstrator Lab Amsterdam and was its director until 2021. He also served as Director for Valorization for the Faculty of Science for two years, before being appointed Chief Impact Officer for the whole university in January 2022.

Your task is to create impact. “To maximize the overall utility of what you develop”

A little trust goes a long way

As soon as you incorporate a company, conflicts of interests inevitably arise. “You can’t avoid it”, says Iannuzzi, “You have to manage it”. And you can. When your university talks to your company, you leave the room. That is one important reason you need an entrepreneur. Not only for the experience they bring, or a skillset to complement yours – but also to represent the company in discussions with your university or research institute. Put your personal interests third, after theirs, and trust them to sort out the use of university resources by the company. Iannuzzi has always been careful to ensure that what his PhDs work on, is purely driven by science and what they need for their doctorates, and that everything done by his PhDs is open science and can be published. He also keeps track of his time, as, in his opinion, should everybody who has prolonged ancillary activities. So long as researchers stay out of discussions between their university and company, are fully transparent and have just a little sensitivity, any conflict of interest will be relatively easily resolved. Protocols and policies certainly help, but nothing beats transparency and trust.

Iannuzzi also has no issue with scientists earning money from the startups they (co-)found. When they try to build a company, they take a huge risk with high opportunity costs. They give up big part of their holidays and free time. They will pay high psychological costs, with many sleepless nights and downswings, not to mention the risk of reputation loss. What drives them, typically, is a passion to move their science beyond the academic world, and that is how it should be. But if, along the way, the adventure becomes profitable, it is fair that they share in the harvest of what they have planted.

“My device was a simple idea”, Iannuzzi explains. If he hadn’t met Hans Brouwer and set up Optics11, that device “would have been used by maybe 10 people”. Now, it is used everywhere around the world. That is the real payoff, any financial return is a collateral effect. Iannuzzi is proud of the former but does not think that he should be ashamed of the latter.

Fiat versus Ferrari

It is not just fair to let the scientists share in the rewards, it is essential. The startup company needs them to be successful. Because they – and sometimes they alone – understand the technology and because of their “brand power”. As they invented it, they can credibly talk about it and inspire confidence in potential users (if the message is put forward in good faith, of course).

The university too benefits from their continued involvement. “The company sells a Fiat 500”, says Iannuzzi, “but I used to have a Ferrari in my lab. More difficult to drive, but way better to win a race. The PhD candidates working with me were able to pioneer new directions because they could have access to superior technologies with respect to Optics11’s average customer”.

Should we be thinking less about potential conflicts and more about potential synergies, then? Iannuzzi certainly thinks so, and he takes that notion further. The idea itself is “maybe 1%”, he says. The rest are typically the non-technical aspects of adopting a new technology, such as consumer behaviour, market-product fit, regulation and societal acceptance or resistance. To be successful, he argues, you need to bring together insights from economics, the humanities, even theology if necessary. And what better place to do that than the campus of a university like VU Amsterdam, that has all these disciplines. We should exploit the richness of the academic environment and work together in interdisciplinary teams to make sure that we provide a common service to a bigger cause.

Iannuzzi sits on the supervisory board of VU Amsterdam’s startup pavilion StartHub and was or is an advisor to the Amsterdam Centre of Entrepreneurship, Dutch Research Council NWO's Faculty of Impact and companies Scailable (AI solutions for various industries) and Dayrize (SAAS tool for impact assessment of consumer products). He teaches courses on entrepreneurship for scientists and, in 2017, he wrote a successful book by the title of Entrepreneurship for Physicists: A practical guide to move inventions from university to market.

In 2018 he received the NWO-Physics Innovation Award.

As soon as you incorporate a company, conflicts of interests inevitably arise. “You can’t avoid it”, says Iannuzzi, “You have to manage it”.

Maximum impact

That bigger cause is impact. “We have a mandate from society”, he stresses. Being an entrepreneurial scientist is not about setting up a lifestyle business, “a professor and a couple of PhD’s, just to make some extra income for our research group or our pockets”. Your task is to create impact. “To maximize the overall utility of what you develop”, as Davide puts it, channelling his inner Bentham.

That utility should be understood broadly. An entrepreneur is usually tasked to develop a product that could maximize the financial return for the people who invest in it – and that is ok, because it typically means bringing that product to as many people as possible, who will presumably benefit from it. And, if successful, the new company will generate new jobs across the supply chain, new capital for reinvestment in further innovation and a just reward to investors for the risk they took. But it could be successful on an even larger scale. In fact, companies can be set up from the start to contribute to both wealth and (global) wellbeing.

Imagine if universities would focus on entrepreneurs and investors who embrace that logic and are committed, as they design, build and deliver a new product, to maximizing their long-term impact on wellbeing at a planetary level – including, through their business model, the wellbeing of people who do not use the product or benefit directly from the sales it generates. Universities could use all their knowledge on the technical and non-technical aspects of innovation, as well as the public resources at their disposal – from access to facilities and researchers to KTO support – to help these companies evaluate their impact, optimize it, grow and eventually outcompete less sustainable rivals.

What better role for universities and their KTOs and who better to play it? It is a tantalizing vision… as befits one of the first university Chief Impact Officers.

Three takeaways for further contemplation and discussion:

- Can we put our trust in simple guidelines and full transparency to manage conflicts of interests when scientists have a stake in companies?

- Should we not focus more on the impact scientists can create with their startups and less on capping any returns they may make as a collateral effect?

- Could maximising the impact on wellbeing be the next evolution/ultimate purpose of universities and their KTOs?